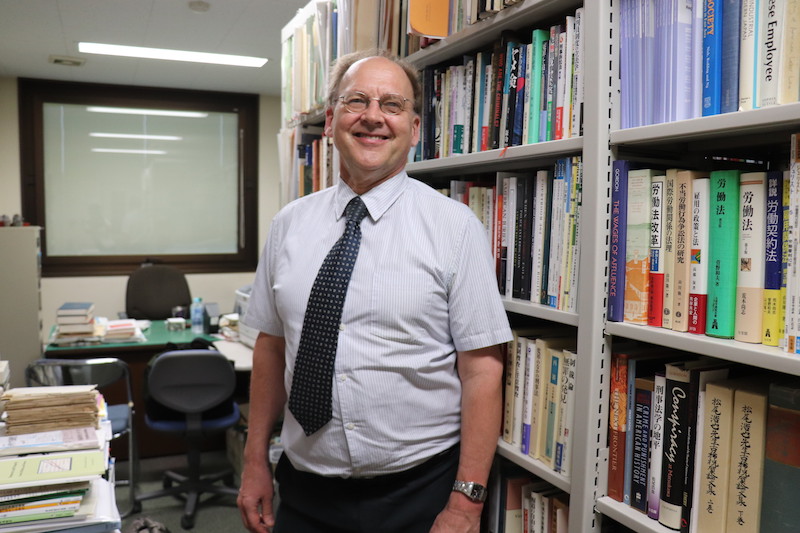

Interviewed and Written by Mon Madomitsu

━━You are now studying the relationship between the legal system and Japanese society, but at Harvard College you majored in East Asian studies. When did you come to have interests in East Asia and Japan?

In World War II, my father worked as a Japanese interpreter after he graduated from the U.S. Navy Japanese Language School. In that school, he was in the same class as Donald Keene, who later became a renowned scholar of Japanese literature. Since my childhood I had been hearing news about Japan from my father and his best friend, who also had been an interpreter and remained in Japan after the war as a journalist; in that sense, I felt an affinity for Japan.

━━Why did you go to Harvard Law School after graduating from college?

Ezra Vogel, who later became well known for the book Japan as Number One, was my mentor in college. He was a truly dedicated faculty member, and initially I thought about following in his footsteps and entering the graduate program, with a view to specializing in Japanese society. I suspect he would have supported that plan and convinced me to follow it. But in my senior year he went to Japan for research. Instead I discussed my future plans with a postdoc who was supervising my graduation thesis. The postdoc was very pessimistic about prospects for academic positions in Japanese studies and said, “Even if you complete the Ph.D. program, you won’t be able to find any decent position.”

So I wondered what to do with my life. I knew I wanted to maintain ties with Japan; and I felt that if I could graduate from a law school and find a position in a law firm that had a Japan practice, I would be able to do that.

━━After graduation from Law School, you gained practical experience in various places.

I served as a law clerk in U.S. District Court and then at the U.S. Supreme Court. During law school I came to realize there might be an alternative pathway to an academic career, as a specialist in Japanese law. In the U.S. setting, having a Supreme Court clerkship makes prospects more realistic for obtaining a teaching position. As preparation for a teaching career, I felt the need to undertake more study and research on Japanese law, and I came to Todai as a Fulbright researcher. I also felt the need to obtain practice experience, which I did by working in the Legal Department at Nissan Motors and at a law firm in New York. Thereafter I was able to obtain a position at the University of Washington. Later, on two occasions I was invited to serve as a visiting professor at Todai, and then I was offered a position as a full-time professor here in 2000.

━━As a requirement of the policy that promotes free education in college, which MEXT presented this year, it is noted that there should be a certain percentage of classes delivered by faculty members who have practical experience. How do you regard such a tendency to emphasize the practical aspects of higher education in recent years?

As a faculty member in law, I have mixed feelings. In the Japanese law school system, there is a division between practice professors and research professors. Very few of the latter have attained practice experience; they are overwhelmingly academic in background and orientation. In the United States, on the contrary, over 90 percent of research professors also have practice experience. I feel that even experts on theory should know how law and policy making work in practical settings. In this sense, I am a strong believer in the value of practice experience.

At the same time, having a broad background in the humanities, including knowledge of classics, literature, philosophy and ethics, is also very important. Such a background is valuable for viewing matters from a wide range of perspectives and getting to the core of issues, and for ensuring sensitivity to the humanistic element of society.

At Harvard College, one of my classmates was the world-renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma. Before he entered college, he already had been performing around the world, so he did not need to go to a music conservatory. Rather, he came to Harvard because he wanted to expose himself to a wide range of ideas and broaden his horizons. Ever since, Yo-Yo has constantly been challenging new genres and undertaking a wide range of activities. As one recent example, I hear that this April he presented a message of criticism against President Trump’s plan to build a wall between the United States and Mexico, by giving a concert along the border between the two nations. As I see Yo-Yo undertake such rich activities throughout the world, I like to think of it as the fruit of the broad horizons he acquired at Harvard.

In sum, while I strongly believe in the value of practice experience, I fear that an excessive emphasis on practical education may lead to neglect for the humanities and liberal arts education, which also are of vital importance for nurturing balanced and well-rounded individuals.

━━From the standpoint of a foreign faculty member, what sorts of issues do you think Todai is confronted with now?

In my view, three issues to which Todai should devote even more attention are internationalization, interdisciplinarity, and diversity. The situation for all three has improved over the past decade, but there still remains much to be done. With respect to internationalization, study abroad of course is valuable for developing understanding of the foreign nation, but from my own experience it is even more important for developing understanding of your own nation. The experience of living and studying abroad leads to an awareness of aspects of your own nation that you previously took for granted. Thus, I am delighted to see that in recent years Todai has begun to encourage students to go abroad. Yet I get the sense students who acquired overseas experiences and came back do not really have many opportunities to share their experiences with other students. There are some places where they can present their experiences, such as in the briefing session for study abroad programs, but there the audience is limited to those who already are interested in studying abroad. I would like to see many more opportunities for students to share their experiences.

Next, with respect to interdisciplinarity, there are opportunities for students to expose themselves to a wide range of academic disciplines through the liberal arts curriculum over the first two years. With regard to research, though, my sense is that the barriers between disciplines remain high. Even within the Law Faculty, there are separate gatherings for faculty in civil law, criminal law, labor law, etc., but few academic events that bring together law and politics scholars from a broad range of fields. While there have been many promising developments, such as the establishment and success of the Graduate School in Public Policy (GraSPP), a joint undertaking of the Faculty of Law and Faculty of Economics, and the recent establishment of the Global Leadership Program, which spans many faculties including the Faculty of Law, I would like to see even more opportunities for interdisciplinary research and study, by faculty as well as students.

━━As for diversity, does it not seem that Todai is endeavoring to increase diversity in such matters as gender and national origin?

With regard to national origin, with the PEAK (Program in English at Komaba) program and other programs for foreign students, there is far greater diversity now than when I first studied at Todai in the early 1980s. With regard to gender, I do not question the sincerity of Todai’s desire to increase diversity; but I am disappointed to see that women still comprise only about twenty percent of all undergraduate students and under ten percent of all professors and associate professors.

One other concern I have is the lack of attention to the importance of diversity in the educational process itself. For instance, when the new law school system was established, in an effort to secure diversity, the law schools, including Todai, were expected to recruit students with work and other societal experience and graduates from faculties other than law (although, notably, there was no mention of gender). At the time, many observers recognized the value of such diversity for the legal profession – having lawyers, for example, with backgrounds in economics, or engineering, or medicine. Yet I largely doubt whether such diversity is made good use of inside classrooms. From my own experience teaching both in the United States and Japan, a diverse student body greatly enhances the learning environment by allowing us to examine the same issue from different perspectives. Taking a law class as an example, students can think what the impact is of a particular law or precedent on women, on minorities, or even on matters such as business innovation, based on their own identities and experiences, and can share their thoughts with other classmates. In this way, diversity in students has great significance for the learning process itself. For this purpose, of course, it is essential to have classes in which students discuss with the professor and among themselves, and not simply one-way lectures.

━━It is regarded as problematic even among the students that there are many one-way lectures given in big lecture halls in the Law Faculty of Todai. However, some people maintain that interactive classes, in which teachers ask students questions and engage in dialogue with the students, are meaningful only in the United States, where judicial cases are central to the law, but are not suitable for Japan, where codes rather than cases are central.

Many people in Japan have seen broadcasts of Michael Sandel’s “Justice” course, in which he engages students in stimulating give-and-take discussions, in large lecture halls packed with several hundred students. He is truly exceptional. Even in the United States, very few professors can effectively conduct discussion-based teaching in classes with 200 or more students.

That said, I flatly disagree with the notion that interactive teaching is not suited to Japan’s code-based legal system. The dialogue-based class practiced in American legal education is referred to as the Socratic Method, but the philosopher Socrates, after all, was not discussing judicial cases. It is a method to deepen your thoughts and thinking process; and its use is not limited to any particular type of contents. As Sandel demonstrates so well in his Justice classes, the method can be very effective for examining concepts, theories, and philosophical debates; and, I would submit, it also can be very effective for considering code provisions and statutory interpretation. As the teacher and students repeatedly engage in back-and-forth questions and answers, students are led to realize that they had not considered all the possible aspects and ramifications of the problem; and, by engaging in this intensive analytical process, students also hone their skill in reasoning and their ability to apply that skill in other settings. By leading students to think for themselves about the many often-hidden aspects of a problem, the dialogue-based class helps develop intellectual self-reliance, the habit of continually probing on one’s own. That, to my mind, is the essence of the dialogue-based class.

━What do you wish for the youth in the next generation?

The University of Washington, where I used to teach, has a slogan, “Question the Answer.” The slogan is not “Answer the Question,” but “Question the Answer.” It means, in essence, do not simply take what you are told as a given, but think for yourselves; think critically, and never stop inquiring.

When I clerked at the U.S. Supreme Court, one of the justices was Thurgood Marshall. He was the first African American to serve on the Supreme Court, and he had been a leader in the civil rights movement, as well. At the U.S. Supreme Court, oral argument sessions are very active; some justices bombard the lawyers with question after question. In contrast, Justice Marshall didn’t ask many questions during the oral argument sessions, but one question that he did ask from time to time was, “But is it right?” When a lawyer was presenting a highly legalistic justification for some narrow interpretation of a statutory or constitutional right, Justice Marshall would ask, in a deep, booming voice, “But is it right, counselor? Is it right?” By this he meant not “Is that a technically justifiable interpretation?”, but rather, “Is it morally right? Is it appropriate? Is it fair? You are giving us this narrow interpretation of the law, but think about the implications of that argument for American society. Isn’t that what we should be focused on?”

I was deeply impressed by Justice Marshall’s attitude. Do not just be content to say, “This is the way things are.” Look beyond, and keep asking, “But is it right?” That’s the sort of attitude I hope you all will take.

(The Interview was conducted in English. The Japanese version is available from the following link.)

真の多様性とは 日米両国の視点をもったフット教授にインタビュー